MoCA Tucson

In 1948, in the icy waters off the west coast of Iceland, a British fishing trawler called the Epine GY7 wrecked. The remains of the ship washed up on a remote beach near the Snaefellsness Glacier.

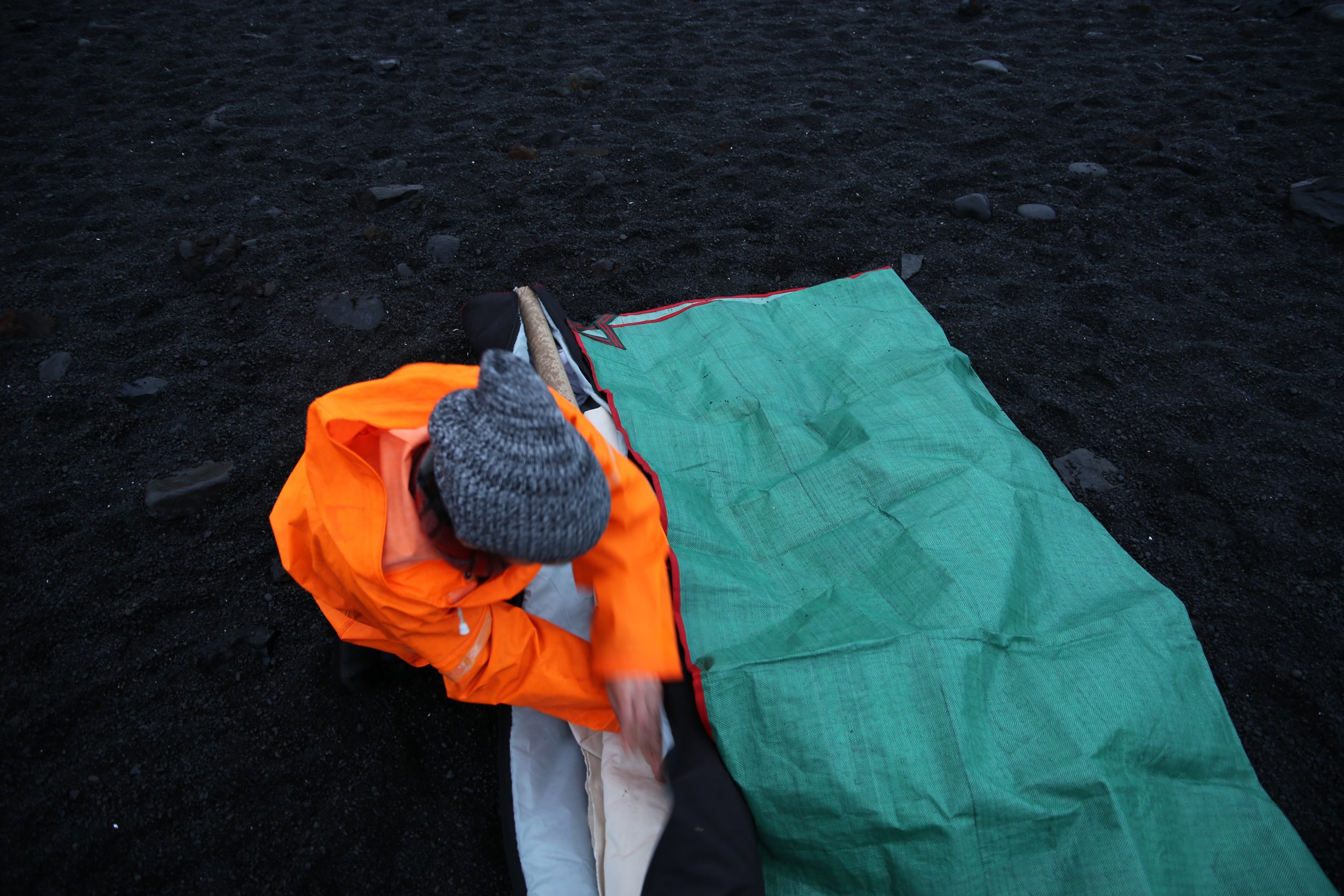

Silverstein documented and archived the three-dimensional fragments of this wreckage into graphic two-dimensional rubbings, which she brought back to her Los Angeles studio in order to create “fantastical reconstructions” of the ship.

Inherent in Silverstein’s practice is this same desire to take apart and piece back together fragments of her own work. Her studio overflows with stacks, piles, and arrangements of shapes cut from larger pieces of painted canvas which she arranges and rearranges into large-scale layered configurations.

This project is also about failure—the epic failure that is a shipwreck is echoed by the secondary, certain failure to “reconstruct” the ship. For many reasons, the artist was always destined to fail at this monumental endeavor. But this frees the project from the obligation of objective reporting and favors what Werner Herzog would call “ecstatic truth.” Art is a response to knowing something is impossible.

The Fantastical Reconstruction of the Epine GY7

In the middle of a winter night in 1948, in the icy, turbulent waters off the western coast of Iceland, a British fishing trawler called the Epine GY7 smashed into rocks. All that’s left of this event is a strange landscape of twisted metal figures embedded in a black-pebbled beach near Snaefellsness Glacier. Unrecognizable as the ship it once was, and left to rust for the past 70 years, these sculptural, oxidized remains create a strikingly enigmatic memorial.

Like the metal strewn on the beach, my studio overflows with stacks, piles and arrangements of abstract cut shapes of painted canvas — a different kind of wreckage. My process is one of assembling and reassembling these fragments of evidence into large-scale configurations that posit new possibilities, forms, and understandings.

I’ve been to Dritvik beach many times. Once, with an ex-boyfriend on a road trip with our friends Hildur and Joi. And then again, about a year later, to scatter that boyfriend’s ashes after he died in a car accident. Each time, I’ve felt compelled to gather the pieces somehow, or make a record of them, and to translate them into a new form: what meaning can I make from this evidence?

Most recently, I went back to Dritvik beach with a small group of loyal and intrepid friends. Over the course of five summer nights, fueled by boxed wine and thermoses of coffee, we made rubbings on canvas of every piece of the rusted remains of the Epine GY7.

When my boyfriend died, I couldn’t make sense of it. I felt that if I just recorded it, gathered the evidence, I could make sense of it later. After a year of documenting — turning my camera on myself, on others, on people I thought might have answers — I had accumulated over 50 tapes. I began to sift through them; I transcribed each one by hand. That document is the catalog of this show.

This project is not an attempt to recreate history, but rather to propose a new monument, a monument of a monument. Not to report but to transform.